When thinking of difficult times for the Swiss watch industry, the troublesome 80s of the previous century are very likely to come to mind. The watch market was flooded with Japanese brands such as Casio, Citizen and Seiko with their digital watches. These were far more accurate than the mechanical watches from Switzerland, equipped with all kinds of new functions (e.g. calculators) and much cheaper.

The Swiss watch industry was able to keep its head above water thanks to the brilliant invention of the Swatch. The mechanical watches gradually got back on their feet again and, in spite of the actual crisis, the sales of luxurious watches doubled in 2012.

However, in the late 18th century, a true war, the so-called watchmakers’ war, was fought between the Genevan watchmakers and the watch empire of the French philosopher Voltaire (1694-1778) at his domain in Ferney, France.

The flourishing Genevan watch industry in the 17th and 18th century was based on a solid commercial organisation in the city and, in addition, the ‘marchands etablisseurs’ who travelled around to buy components and assemble watches.

It all looked well enough on paper, but in reality there were many abuses, socially, economically, politically, resulting in quite some watch makers emigrating to more hospitable places. All this was caused by the inflexible rules and regulations of the ‘Corporation des horlogers genevois’ which had the exclusive rights to employment.

Eventually the Genevan watch industry got beaten at its own game. Talented watchmakers took up their residences in other cities and countries and started exerting their influence from there. They settled along Lake Leman, in the valleys of the Jura, Vaud and Neuchatel and the Erguel region of the canton of Bern. An even more serious threat to Geneva were the competitive watch producing centres in Moscow, Montbeliard and Pforzheim.

Voltaire had come to Geneva following the steps of the well-known physician Theodore Tronchin (1709-1781) and resided in his Genevan house ‘Les Delices’ from 1755 to 1760. Voltaire built a good relationship with the ‘cabinotiers’, the independent watchmakers who, like himself, were greatly interested in actual items on which they conducted lively debates.

Voltaire took actively part in the Genevan conflict between the citizens and the ‘natifs’, an underprivileged group of people who were original Genevan inhabitants. Voltaire encouraged them to rebel and also invited their leaders. As a consequence the relationship between Voltaire and Geneva was flagging and in 1758 Voltaire bought an estate in Ferney (F). Once moved and settled into his new home, he accommodated the Genevan ‘natifs’ and planted orchards and vineyards in fallow land. Voltaire developed more and more into an industrialist investing in tannery, a tile oven, pottery and factories producing silk stockings, lace and ceramics.

Pic.: Voltaire’s estate in Ferney in the 18th century

In 1766, the Republic of Geneva refused mediation for its internal conflicts, which was suggested by France and the large Swiss cantons. The French minister Choiseul then continued his economic war against the Republic, at the Versailles Court known as the ‘watchmakers’ war’, until 1769.

In the year 1770 a Genevan enactment offered the ‘natifs’ two options: either take an oath of loyalty and remain in the city or leave. Moreover, the city threw agitators out without mercy. Among them were the watchmakers Edouard Luya, Louis Philippe Pouzait, Pierre Rival and Guillaume Henri Valentin.

Choiseul had tried to start a new watch factory in Versoix, but in December 1770 he lost favour definitely and a substantial number of watchmakers who had not returned to Geneva sought the support of Voltaire in Ferney.

These developments led to opening the attack to the ‘Fabrique’ by Voltaire and he warmly welcomed the exodus of protestant watchmakers to the Catholic Gex district.

Ferney-Voltaire quickly developed from a few houses into 20 and eventually about 100. The ‘cabinotiers’ set to work in an old barrel which was equipped with benches and the factory was run by the watchmakers Pierre Dufour and Louis Ceret.

The high days of the Ferney “royal” (it never obtained this title officially) watch factory covered the period between 1770 and 1778. It appears from various letters that in that period the number of employees had grown from 40 to 1,200.

The first watches were ready in April 1770 and on the ninth of this month Voltaire wrote to Fr. de Caire that “they, although just started, had already enough watches to send to Spain in a small box. This is the beginning of a very large company”. Watches were sent to the Duke and Duchess of Choiseul, Voltaire’s patrons, and to the King. In ’70, ’71 and ’73 watches were also offered to the Versailles Court for royal weddings, but the majority of these consignments were not paid for.

The watchmakers worked in five other factories as well under the direction of partnerships: Pierre Dufour and his brother-in-law Louis Céret, Louis Servant and Antoine Boursault, Guillaume Henri Valentin and Antoine Dalleizette, Panrier and Mauzié, and Georges Auzière and his brother, for watch cases. Although none of the watches had the Voltaire signature, they all bore the name of Fernex, Ferney, Fernaix or Ferney Voltaire in Europe.

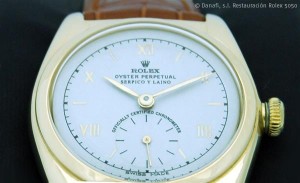

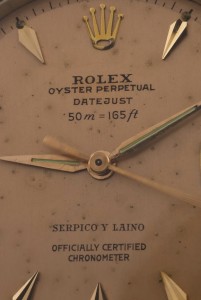

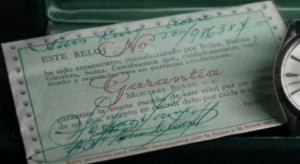

Pic.: a watch made by Georges Auziere (1713-1799) in the eighties of the 18th century; it had a Ferney Voltaire, Mestral signed clockwork

Voltaire offered the watchmakers free loans and provided them with raw material, particularly gold. In this way he served as an ‘etablisseur’ according to the Genevan model and invested his large fortune in the company. Important part of his battle against the ‘Fabrique’ was that he had made arrangements with French Post for free consignments of Ferney watches.

An example of Voltaire’s marketing efforts is the following letter of the 20th of December 1771 to the Count of Aranda, a Spanish minister: “Should you wish to adorn the finger of a distinguished Spanish lady with a ring watch showing the seconds and repeating the quarters and half hours on a carillon, all decorated with diamonds, such a watch is only made in my village, and we are at your disposal. It is not vanity that makes me say this, since it was pure chance that brought me the only artist [probably watchmaker Jean François Auzière junior] who makes these little marvels – marvels that are not likely to disappoint you”.

The famous watchmaker Jean-Antoine Lepine worked for Voltaire until 1774 and after that he went to Paris to open his own shop in the Place Dauphine. The Lepine calibre, developed in 1775 or so, was used in Ferney.

The hardest problem Voltaire’s company faced was selling. In Spain and Turkey Geneva still held a position of authority. He approached Catherine II from Russia to help him conquer the Chinese market and the Tsarina became Voltaire’s best customer.

Voltaire used his network to the maximum illustrated by the following circular letter he wrote to the French ambassadors (5-6-’70):

“Sir, I have the honour of informing Your Excellency that Geneva’s burghers having unfortunately assassinated some of their fellow countrymen, several families of good watchmakers have taken refuge on a small estate I own in the Gex region, his Grace the Duke of Choiseul having placed them under the King’s protection. I have had the good fortune to enable them to practice their talents. These are Geneva’s best artists. They do work of all kinds and at a more moderate price than any other factory. They can very quickly do any enamel portrait for a watch case…”.

Voltaire praised his watches by saying that they were at least so good as those from London, Paris or Geneva and that, in addition, their price was 2/3 lower than the prices customers paid in Paris. However, Voltaire’s customers were poor payers.

The catalogue contained a large number of types of watches exposed for sale: gold (18c versus 20c in Paris), enamelled watches, precious stones, clockworks with second hands, cylinder echappements, silver (lower carate than the competitors) and imitation stone and marcasite decorated. The enamelled types were concentrated on landscapes and portraits.

The quality of the clockworks varied. It appeared from an anonymous letter from 1773 that the Ferney workplaces produced approximately 4,000 watches annually (ca. 400 watchmakers), whereas Genevan ‘Fabrique’ produced 33,000 watches on an annual basis (5,000 watchmakers).

In 1775, the Ferney watch empire got into trouble by laborious negotiations for obtaining raw material and for various fiscal matters. In 1776, a watchmakers’ exodus from Ferney took place because the Genevan conditions had substantially improved. Simultaneously, Voltaire lost his interest in the watch industry. In Februari 1778 he moved to Paris in high expectations, but in May of the same year he died.

After his death efforts were made to restore Ferney to its previous glories. Historically interesting is that, in 1793, the world-famous watchmaker Abraham Louis Breguet was asked to save the factory, but he did not really succeed.

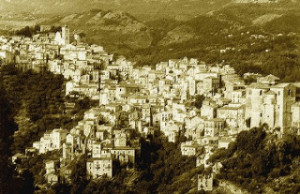

Pic.: the actual Ferney-Voltaire

Jaap Bakker