Ernest Hemingway: a true Rolex man

The quintessential Renaissance man, Ernest Hemingway was a Nobel-prize-winning author, war reporter, bullfighter and a sophisticated cocktail connoisseur. He lived (and drank) all over the world, but was oft known for hanging out in bars in Key West and Havana. We’re toasting Hemingway this month, in honor of his birthday (July 21), with a few tidbits and tipples.

The Cocktails:

The original Hemingway Daiquiri was a frozen mixture of white rum, lime and grapefruit juice and maraschino liqueur and was reminiscent of a lime-colored Slurpee. Served at the infamous El Floridita in Cuba, it is said Hemingway once consumed more than a dozen in an evening. He remarked that one “felt as you drank them, the way downhill glacier skiing feels running through powder snow.” Ordered mostly by Hemingway as a double, the drink also became known as the Papa Dobles. Nowadays, the cocktail is often served straight up, no blender required. Hemingway was also a fan of absinthe and is credited with mixing a potent blend of absinthe and Champagne dubbed Death in the Afternoon after his 1932 book of the same name.

His Drinking Buddies:

In Paris during the “Golden Age” of the 1920s, Hemingway drank with a bevy of famous artists and writers including Pablo Picasso, F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce and W. B. Yeats. Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris reenacts the conversations and carousing with admirable detail, as does our top tome of the month, The Paris Wife, a fictional account of Hemingway’s first marriage during those party years.

Hemingway Daiquiri

SERVES ONE

2 ounces white rum

3/4 ounce fresh lime juice

1/2 ounce fresh grapefruit juice

1/2 ounce maraschino liqueur

Add all ingredients to a cocktail shaker filled with ice and shake well. Strain into a chilled coupe or martini glass and garnish with a lime wheel.

Death in the Afternoon

SERVES ONE

1 1/2 ounces absinthe

4 ounces Brut Champagne

Pour absinthe into a champagne flute and top with chilled Brut Champagne until it clouds over.

The above text reflects in a nutshell the type of man Ernest Hemingway was and what kind of life he lived. However, this is only one side of the story. Hemingway suffered from bipolar disorder and had severe depressions. In 1960 Hemingway was treated with ECT (‘Electro Convulsive Therapy’, “Electroshock”) in the Mayo Clinic, about which he said: “What these shock doctors don’t know is about writers…and what they do to them…What is the sense of ruining my head and erasing my memory, which is my capital, and putting me out of business? It was a brilliant cure but we lost the patient.” Eventually, in Idaho in 1961, he ended his life by shooting himself in the head; the way in which he committed this act is completely in line with Hemingway’s character.

This 1929 Rolls Royce Phantom II Short Coupled Saloon used to belong to Ernest Hemingway. With this car he traversed the USA while writing and publishing ‘A Farewell to Arms’, ‘The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories’, and ‘Death in the Afternoon’. The car is provided with compartments for booze, golf and hunting stores.

Another car owned by Hemingway is the Lancia B10 with which he travelled through Europe in 1954.

Ernest Hemingway, who famously wrote standing (“Hemingway stands when he writes. He stands in a pair of his oversized loafers on the worn skin of a lesser kudu—the typewriter and the reading board chest-high opposite him.”), approaches his craft with equal parts poeticism and pragmatism:

” When I am working on a book or a story I write every morning as soon after first light as possible. There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and warm as you write. You read what you have written and, as you always stop when you know what is going to happen next, you go on from there. You write until you come to a place where you still have your juice and know what will happen next and you stop and try to live through until the next day when you hit it again. You have started at six in the morning, say, and may go on until noon or be through before that. When you stop you are as empty, and at the same time never empty but filling, as when you have made love to someone you love. Nothing can hurt you, nothing can happen, nothing means anything until the next day when you do it again. It is the wait until the next day that is hard to get through “.

In the Winter of 1917 the Red Cross started a campaign for the recruitment of American volunteers who would drive ambulances at the Italian front. Hemingway applied for the job, because the American army refused to take him into service due to a bad eye. On 8 July 1918, only a few weeks after his arrival, he suffered leg injuries inflicted by shell-splinters while distributing chocolate and cigarettes among Italian soldiers along the river Piave. According to Ted Brumback, another ambulance driver, who wrote Hemingway’s father a letter, more than 200 splinters pierced Hemingway’s legs, but he managed nevertheless to get another wounded soldier to the first-aid post. On his way his legs were hit by machine gun bullets on top. Later, for this act of self-sacrifice he was rewarded the Italian Heroism Silver Medal. His right knee was injured so badly that he feared amputation. Recovering from his injuries in a Milan hospital, Hemingway fell in love with Agnes von Kurowsky, a well-educated American nurse who was eight years his senior. Hemingway would incorporate this romance in his novel ‘A Farewell to Arms’.

Ernest Hemingway wrote ‘For whom the bell tolls’, about his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, in 1939 in Cuba, Key West and Sun Valley, Idaho

The book tells the story of Robert Jordan, a young American explosive expert, who as member of the International Brigades is added to an antifascist guerilla unit in the mountains during the Spanish Civil War. Jointly they have to blow up a bridge in order to make an attack on Segovia a success. During this mission Jordan falls in love with Maria, a girl who had lost her parents in the war.

The book is partially autobiographic, Hemingway was in Spain during the civil war. The main character may be based on Robert Hale Merriman, an American who was killed in Spain in 1938. Merriman was an acquaintance of Hemingway’s.

In WO II Hemingway was a reporter in war areas in Europe and the below text is about his experiences in Belgium in those days:

On September 11th, 1944, Colonel Charles Trueman Buck Lanham, with a smouldering Lucky Strike permanently dangling from the left corner of his mouth, was looking through a splendid pair of captured German Zeiss field-glasses toward the river that formed the German border less than a hundred yards away.

“ Damn!”

“ What’s the problem, Buck?” asked Hemingway, who was playing a hand of gin rummy with Pelkey.

“ They’ve blown the damned the bridge. That was obviously the explosion we heard a minute ago.”

“ Who the hell are “they”, Buck?”

“ The damned SS. We heard yesterday that a few remnants of the 2nd SS Division might have been left behind to the give the regular German army a chance to get home to father.”

“ A joker don’t count, Archie. What can we do, Buck?”

“ Repair the bridge, I guess.”

Lanham then spotted one of his aides and yelled.

“ Captain!”

“ Sir?”

“ Get a bunch of engineers up here, and fast.”

“ Yes sir, but they’re way back…”

“ I didn’t ask where they were, captain, just get them up here.”

“ Yes, sir!”

The Captain roared off in his Jeep as Hemingway placed his cards on top of the low wall he and Pelkey were using as a card table.

“ Four, five, and six of clubs, oh, and eight, nine, ten, and jack of hearts. My hand I think, Archie? That’s a hundred dollars you owe me.”

“ Shit.”

Hemingway, Pelkey, and their little band, plus Lanham and a forward reconnaissance unit of his 22nd, were in the Belgian town of Houffalize – to the south of Liege, and just north of Bastogne – deep in the valley of the River Ourthe, beneath steep grey granite cliffs, which was, in the words of British historian Charles Whiting, “…the centre of a small road network and a bottle-neck. In three months time it was to be the centre of the great link up between the 1st and 3rd US Armies during the Battle of the Bulge and then it would be wrecked completely.”

For Lanham the bridge across the Ourthe, in the middle of the town, was essential for the eastward progress of the 22nd. But that didn’t bother the inhabitants of the town, who – even though many of their houses had been destroyed as the bridge went up – still heaped gifts of cakes,

eggs, and bottles of wine, upon Hemingway and the rest of the “liberators.”

“ Say, Ernie, if this were Oak Park, and your dear Mother was being liberated, would she offer cakes and wine?” asked Lanham.

“ I don’t ever remember seeing cakes in the house, sure as hell don’t recall eating any. And as for wine Buck, no chance, the Devil’s liqueur. No, any liberating army outside the Bitch’s house would be told in no uncertain terms to please stay off the grass and to be as quiet as possible so as not to disturb her afternoon nap. But then, who’d want to liberate Oak Park?”

After frying and devouring the eggs, eating the cakes, and drinking the wine, Lanham got the now assembled bunch of 22nd Infantry Engineers (the captain had found them brewing coffee less than three miles down the road) to gather together as many villagers as they could to start rebuilding the bridge with anything they could lay their hands on.

“ Wish I could get my hands on a Bailey Bridge, Ernie, but the damned Limeys keep them all to themselves, and the few the US have are in Holland.”

“ To hell with the Limeys, Buck.”

“ Yeh, but I still wish I had one of their damned bridges.”

Donald Bailey (later, Sir Donald) a pretty low grade British civil servant – and something of a Meccano fanatic as a boy – invented his so called Bailey Bridge in 1941, and eventually convinced the British military to take up his idea; and like all simple ideas it proved itself to be indispensable.

In essence a Bailey Bridge is a prefabricated metal road bridge that floats on pontoons, with the roadway element made-up of heavy duty timber planks. It can be assembled relatively easily, taking

around six hours to span a river the size of the Thames. The first was erected (under heavy enemy fire) in May 1944, at the battle of Monte Casino in Italy. Hundreds were used in the hours, days, and weeks after D-Day, enabling the Allied armies – especially the heavy armour and supply trucks – to maintain their necessary momentum whenever they came across a destroyed bridge. The Americans soon saw the usefulness of the invention and built hundreds under licence for their own use. As Colonel Lanham mentioned, by September of 1944 virtually all of the Bailey Bridges were being used in Holland as the Allied armoured divisions dashed toward Arnhem to relieve the besieged units of the British Airborne. To get an idea of how a Bailey Bridge was constructed, watch Sir Richard Attenborough’s superb 1977 film, A Bridge Too Far, and enjoy Elliott Gould’s wonderful portrayal of an unconventional, Colonel Lanham style, cigar-chewing American officer kicking ass. Of course Lanham had no chance of getting his hands on a Bailey Bridge, having to make do and mend. Bailey Bridges are still manufactured today.

Hemingway chose not to help re-build the bridge, but instead sat on a fence watching, drinking, and shouting orders on bridge-building techniques. Many of the town’s inhabitants, who genuinely thought Hemingway was in charge, immediately started referring to him as the General. Hemingway told them he was not a general, only a captain, and after being quizzed as to why he held such a lowly rank replied in deliberately broken French:

“Can’t read nor write is why. Never quite got around to it, but hell that don’t hold anyone back in the good old US Army.”

Ernest Hemingway was, as ever, enjoying himself hugely, and Lanham never told the Houffalizeans who was really in charge; why confuse them when they were building such an excellent bridge?

In fact it took less than an hour for the good people of Houffalize to rejoin the two halves of the bridge, and by early evening Lanham’s vehicles were crossing over in numbers – including tanks – to the German side and the inevitable confrontation.

A little further down river – where the Ourthe becomes the Sure – at the village of Stolzemburg, on the Luxembourg side of the river, which forms the border between Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany, a young American Staff Sergeant, Warner H. Holzinger of the US 5th Armoured Division, took a patrol across the river – the bridge there had also been blown by the retreating Germans – and, avoiding the road, scaled the cliffs on the German side. They were the first allied soldiers to enter Germany in wartime since Napoleon’s invasion 150 years before. When they reached a small plateau fifty feet from the top of the cliffs they came across several empty camouflaged bunkers which were being used as a chicken coops by a farmer.

“ Well, if this is the famous West Wall, I don’t think much to it,” Holzinger said to a corporal at his side.

But when his patrol finally reached the cliff top and looked downward toward the heart of Germany they saw hundreds of pillboxes and bunkers of every shape and size. They hit the dirt expecting a barrage of fire, but nothing happened, not a single shot came their way. With night coming on Holzinger didn’t feel like hanging around and ordered his patrol back down the cliff and across the river. He had no desire to see if those other bunkers were empty or not.

When the sergeants report reached General Courtney Hodges, Commander of the US 1st Army, the General issued the following statement:

“ At 1805 hrs on 11th September, a patrol led by Sgt Warner H. Holzinger crossed into Germany near the village of Stolzemburg, a few miles north-east of Vianden, Luxembourg.”

As Warner and his patrol celebrated with a few drinks, and Colonel Clarence Park, Patton’s Inspector General, began to assemble and co-ordinate the paperwork for the interrogation of Ernest Hemingway, the novelist himself went to bed early, after a good dinner, and dreamed of

hunting deer in the forests around Lake Michigan, countryside that was not unlike that around Houffalize.

The morning of Tuesday the 12th September 1944 was clear and sunny, and as Hemingway awoke slowly from a dream where he was hunting deer with his son Patrick in Idaho, and had this most wonderful young stag clear in his sights, and was about to squeeze the trigger and put a .45 shell

cleanly into the back of the animal’s brain, the deer turned his head and looked at Hemingway, and his dark doleful eyes and trusting soft eared head turned into the anguished depressed face of Hemingway’s dead father. Ernest squeezed the trigger anyway.

Hemingway was awake now and looking up from his bed at his ageing face in the cracked oval mirror that hung above the large pine dressing table that stood against the wall in front of the bed of the first floor bedroom of the hunting lodge he, Pelkey, and the others were sharing. Hemingway then looked at his watch, six am, and not a sound except some distant snoring, and the sound of a million animals and birds stretching their wings and limbs amongst the trees and undergrowth

of this part of the dense Ardennes Forest. Funny, Hemingway thought, how, in the midst of war, nature continued to do what nature does, which is preen and sing, and scratch, and burrow, and eat, and fornicate and kill, and be killed. Not so different really to what the rest of the world was doing on this beautiful September morning.

Ernest Hemingway wanted to get up but decided against it for the minute and luxuriated a little longer in the warmth and softness of the feather mattress and fell asleep again, and dreamed, and dreamed of seeing James Joyce…

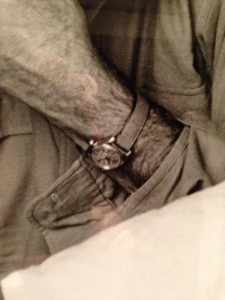

The picture of the Bubbleback was made in the Ralph Lauren dressing room on Worth Avenue in Palm Beach, Florida.

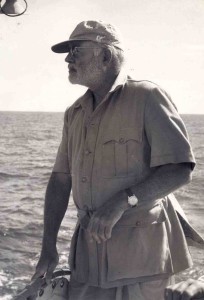

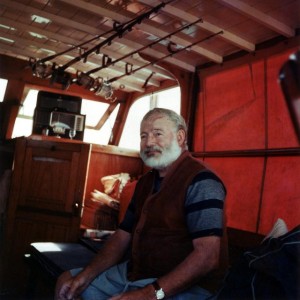

Ernest Hemingway in the cabin of his boat El Pilar. Around his wrist probably an 18c golden, leather band Rolex Oyster from the 1950s

Seeking help about the Rolex watches owned by Hemingway at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston unfortunately gave no new information about these specific watches. They didn’t find any Rolex watch in their Ernest Hemingway Archieve. The only three watches listed by them are the following:

1. Jewelry. Pocket Watch. Gold, metal, glass. Gold pocket watch with second hand dial. Glass face plate is broken. MO 2002.29

2.Jewelry. Pocket Watch. Silver. Silver pocket watch with viello on reverse and “Willoughby A. Hemingway, Dec. 25, 02″ inscribed on interior backing. Face plate is missing. MO 2002.29.3

3. Jewelry. Watch. Metal, plastic. 1 ½ in. Swiss wrist watch with plastic cover. Wrist strap is missing. MO 2002.23.2

Another interesting watch owned by Hemingway, also not a Rolex, is the 1906 Hamilton pocket watch that actress Ava Gardner gave Hemingway for his 55th birthday in 1954. The following article tells the whole story:

Hemingway “Birthday” Pocket Watch

In Cuba in 1951 Hemingway wrote one of his best-known novels ‘The Old Man and the Sea’. Published in 1952, it was Hemingway’s final important fictive work to be published during his life. The story is about Santiago, an old fisherman, who did not catch any fish in 84 days. The parents of his pupil Manolin do no longer allow the boy to accompany him, he must join more successful fishermen, but the boy does not stop looking after the old man. In the evening he will bring Santiago food and they will talk endlessly about the famous American baseball player Joe DiMaggio.

That night Santiago tells the boy that the next day he will sail on his own as far as the Gulf Stream, north of Cuba in the Straits of Florida, and his ‘salao’ (the greatest misfortune) will be over. On day 85 at noon Santiago has a bite, a big fish and he strongly believes the fish to be a marline.

A struggle develops which will last three days and when the fish has finally been attached to his boat, Santiago is exhausted and almost delirious. While he is figuring up how much money this marline will bring him in, the first sharks appear, attracted by the trail of blood behind the boat. Santiago succeeds in beating off the first five sharks, but they continue returning. Eventually, he returns to the port with only the huge skeleton of the fish. When worried Manolin visits him that night, Santiago is asleep, dreaming about his childhood, lions on an African beach.

In 1953 ‘The Old Man and the Sea’ was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the book contributed largely to the Nobel Prize for Literature awarded to Ernest Hemingway in 1954.

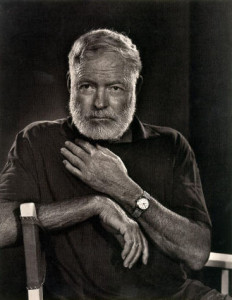

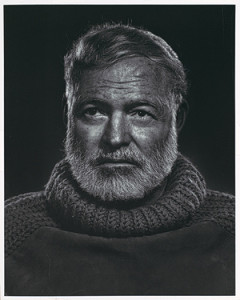

Ernest Hemingway’s portrait was taken by the photographer Yousuf Karsh in 1957. Around his wrist he wears a steel Rolex Oyster Perpetual from the 1950s. The words that accompany the photo are the following:

‘He did not like to talk about his work. Once he had written a book, he said, it went out of his mind completely and no longer interested him. “I must forget what I have written in the past, before I can project myself into a new work.”

What did he think, I asked, about the large tribe of writers who imitate his style? The trouble with imitators, he said, was that they were able to pick out only the obvious faults in his work; they invariably missed his real purpose’.

Karsh’s comments on the photo:

‘I expected to meet in the author a composite of the heroes of his novels. Instead, in 1957, at his home Finca Vigía, near Havana, I found a man of peculiar gentleness, the shyest man I ever photographed – a man cruelly battered by life, but seemingly invincible. He was still suffering from the effects of a plane accident that occurred during his fourth safari to Africa. I had gone the evening before to La Floridita, Hemingway’s favourite bar, to do my “homework” and sample his favorite concoction, the daiquiri. But one can be overprepared! When, at nine the next morning, Hemingway called from the kitchen, “What will you have to drink?” my reply was, I thought, letter-perfect: “Daiquiri, sir.” “Good God, Karsh,” Hemingway remonstrated, “at this hour of the day!”’.

In the book titled ‘Across the river and Into the Trees’ (1950) Hemingway writes the following about a Rolex Oyster (p 117-118):

‘ “It’s just a muscle,” the Colonel said. “Only it is the main muscle. It works as perfectly as a Rolex Oyster Perpetual. The trouble is you cannot send it to the Rolex representative when it goes wrong. When it stops, you just do not know the time. You’re dead.”‘.

Jaap Bakker

Leave a Reply