The 2013 Rolex Daytona Platinum: a future classic

At Baselworld 2013 Rolex introduced the Daytona ref. 116506 to celebrate 50 years of Daytona’s. Unfortunately for the many hoping that Rolex would come with a version in steel (some were talking about a re-edition of the Paul Newman Daytona) that would be affordable for most people Rolex took a different path.

The new Daytona is made of platinum, for the Daytona a first time, and therefore an instant, if expensive, ‘Vintage Rolex’ that will be interesting for collectors. Price wise (est. price: 60,650 euro) it is directly at the level of some of the very collectable Daytona’s from the past.

Besides the use of 950 Platinum there are two things of the Daytona that draw direct attention.

The dial is in ‘ice blue’, a colour that until now was only used for the Day-Date II in Platinum.

Also remarkable is the bezel in ‘chestnut brown’. The bezel is made of Cerachrom, a bezel in one piece. The problem with a common bezel is that it can get scratches or loose it’s beautiful radiance because of chlorine water in a pool, sunlight or salt water. A bezel made from Cerachrom doesn’t have these problems because it’s made from extremely hard ceramic material. Because of this it’s almost impossible to scratch and not sensitive to UV radiation.

The numbers and the scale on the bezel are engraved into the ceramic material before it gets it’s final extremely hard composure by heating it to a temperature of 1,500 grades Celsius. The next step is an illustration of true craftmanship, the bezel, atom by atom, is covered by Platinum or gold and finally it’s polished in order to remove all metal that is not inside the numbers and the scale on the bezel. It causes no surprise that it takes 40 hours to fabricate this bezel for eternity.

Putting the Platinum Rolex on your wrist you directly feel that this is something special, the weight of the watch being 183 gram.

The history of Platinum

Pic.: Platinum crystals

Pic.: Platinum nugget

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atom number 78. The name comes from the Spanish term ‘platina’ which means ‘little silver’. It is a compact, forgable, extendable, precious grey-white transitional metal. It is one of the rarest elements in the layers of the earth and it’s average density is 5 mu grams/kg. South-Africa is responsable for 80% of the world production.

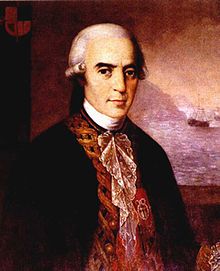

Pic.: Antonio de Ulloa is seen as the discoverer of Platinum in 1735

Platinum was used by the pre-Colombian Americans in the area of today’s Esmeraldas, Ecuador to produce artefacts of a white gold-platinum alloy. The first European reference to Platinum dates from 1557 in the writings of Italian Humanist Julius Caesar Scaliger describing an unknown precious metal found between Darien and Mexico, “which no fire nor any Spanish artifice has yet been able to liquefy”.

In 1741 Charles Wood, a British metallurgist, found different samples of Colombian Platinum in Jamaica which he sent to William Brownrigg for further research.

Antonio de Ulloa returned to Spain in 1746 after being away for eight years on the French geodetic mission. In his report of the mission he described Platinum as non dividable and non calculable. He also predicted the discovery of the Platinum mines.

In 1750 Brownrigg presented a detailed report of his findings with Wood’s Platinum to the Royal Society. It was the first time that Platinum was mentioned in official papers and he also mentioned the extreme high melting point of the metal.

In 1786 Charles III of Spain gave Pierre-Francois Chabaneau a laboratory and a library to be able to do further research of Platinum. Chabaneau managed to remove several impurities from the ore, like gold, mercury, lead, copper and iron. After months of testing Chabaneau managed to produce 23 kilos of pure, forgable Platinum by using hammer and pressure when the metal was white-hot.

Chabaneau realised that the properties of Platinum would give value to objects made from it and together with Joaquin Cabezas he started a business that produced Platinum blocks and kitchen apparel. This was the beginning of what is known as the ‘Platinum Age’ in Spain.

Pic.: 1,000 cubic centimeters of 99,9% pure Platinum which, at the 14th of July 2012, had a worth of appr. $970,600

Platinum, together with the rest of the Platinum metals, is a commercial byproduct of nickel and copper mining. When copper is put under electricity precious metals like silver, gold and the Platinum metals sink to the bottom of the cell where they form an ‘anode sediment’. From the sediment the extraction of the Platinum metals takes place.

When one finds pure Platinum in the ore there are different methods to remove the impurities.

Because of the high density of Platinum lighter impurities in the fluid can be separated and because Platinum is non-magnetic nickel and iron can be removed. The high melting point of Platinum gives the opportunity to remove other metals using heat. Platinum is resistant to hydrochloric and sulfate acids so this can also be used to remove impurities.

A fitting method to purify raw Platinum, existing of Platinum, gold and other Platinum metals, is to work it with ‘aqua regia’ in which palladium, gold and Platinum are solved while osmium, iridium, ruthenium and rhodium do not react. Gold is bound to Fe3-chloride and is filtered after which ammonium-chloroplatinate is formed. By heating this one gets pure Platinum.

In 2010 245 tons of platinum was sold of which 113 (46%) for emission control devices in cars and 76 (31%) for jewellery. The rest, 35.5 tons, was used for investments, electrodes, cancer medication, oxygen sensors, spark plugs and turbine engines.

During periods of economical stability and growth the Platinum price is about twice as high as the gold price but during periods of uncertainty lowers under the gold price; this effect is caused by a declined industrial demand for Platinum. All in all gold is considered a safer investment because it doesn’t depend on industrial factors.

In the 18th century King Louis XV of France declared Platinum to be the only metal fit for a King because of it’s rareness.

The attractiveness of Platinum in jewels, usually a 90-95% alloy, is caused by it’s inertia and radiance. Publications in the jeweller’s business advise jewellers to commend highly of small superficial scratches (‘patine’) as an attractive phenomenon.

Jaap Bakker

Leave a Reply